About Us

Civil War

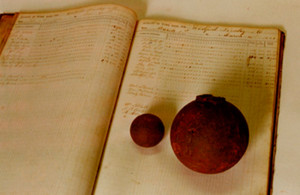

Whitfield Bradley & Company, predecessor of the present-day Clarksville Foundry, produced cannon balls during the Civil War.

The Foundry’s Connection to the Civil War

By Ellen Kanervo

Tennessee founding father James Robertson and his partners established the first iron furnace in the Western Highland Rim region in 1797. By the 1830s Tennessee iron had earned a reputation, according to 19th century ironmaster George Lewis, as being “superior to all other makes in America” and equal to iron from Sweden and Scotland. To back up this claim, Lewis noted that of the many explosions of boilers upon Western and Southern steamboats, resulting in the destruction of thousands of lives, “not one boiler made of Tennessee iron has ever exploded.”

By the 1850s, Lewis reported, 20 furnaces, 10 forges and two rolling mills operated along the Cumberland River, producing annually 30,000 tons of pig metal, 10,000 tons of blooms, and 5,000 tons of bar and boiler plate iron, valued at $1.7 million and employing 3,500 men. Montgomery County alone boasted seven blast furnaces, tuning out 8,000 tons of pig iron a year. But most of this iron was shipped to other states to be cast into usable items; the area had few foundries to mould the pig into cast iron products.

So, in the winter of 1854, Clarksville entrepreneur H.P. Dorris began construction of a foundry on Commerce Street near the city spring. “We made the first iron on 16 August 1854 at 40 minutes after 12. So be it,” wrote an interested observer. Thus was born the ancestor of the modern Clarksville Foundry and Machine Works.

Dorris was assisted in the early years by John P.Y. Whitfield, a native of Philadelphia who, although not yet 30 years old, had gained wide experience in foundry work. After three years Dorris sold the business to Whitfield and two partners, and the firm took the name Whitfield and Co. In 1858 it became Whitfield, Bradley & Co. when Larkin Bradley and James Clark bought out Whitfield’s partners. The 1859-60 Clarksville city directory lists Daniel Wilkinson as a fourth partner. The directory also lists eight employees: three moulders, two machinists, a blacksmith, a carpenter and a general laborer. (Note: there could have been as many as 17 employees counting the partners and a number of moulders and machinists who did not list place of employment.)

Dorris had specialized in iron stoves and fire grates, but the new managers diversified the company’s activities, manufacturing breechings, copper pipes, kettles, sheet iron, and machinery castings of all descriptions, as well as stoves. The company also repaired steam engines and farm machinery; offered complete blacksmith services; and engaged in roofing and guttering.

But at the onset of the Civil War, the foundry’s diversification took a more deadly turn. At the beginning of hostilities, the South had only one working cannon foundry, Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia. Thus it was imperative for Southern foundries to convert to the production of cannon and shot to support the war effort. Although prior to 1861, Tennessee had no cannon foundries, the state became a major producer of cannons for the Confederate Western Division. Whitfield, Bradley & Co. was one of 10 Tennessee foundries known to have produced cannon for the Confederacy.

Montgomery County historian Ursula Beach noted in Along the Warioto, “The Commerce Street foundry of Whitfield, Bradley and Company in July [1861] was producing cannon, six and nine pounders” (p179). The poundage refers to the weight of the projectiles these guns could fire. In battle a six-pounder battery usually contained four six-pounder guns and two 12-pounder howitzers.

Beach continued, “They also manufactured ball, canister and grapeshot” (p179).

Grapeshot, or a stand of grape, was a projectile consisting of a cast iron bottom and top plate with a specific number, usually nine, of cast iron shot arranged in three tiers. When the grape was fired, it broke apart and spread with a shotgun effect. Grapeshot was used at relatively close range against advancing enemy, but, by the time of the Civil War, it had been almost wholly replaced by canister.

A canister was a metal cylinder packed with small balls. Canister was designed to be used close range against enemy troops with the desired effect being that of a huge shotgun blast.

On December 9, 1861, the Confederate government contracted with the foundry to take over work begun by T. M. Brennan & Company on some number of six-pounder iron guns. When Brennan’s machine shop was damaged by fire, he sent between six and 14 rough castings to be machined by Whitfield and Bradley.

Prior to 1860 most cannons manufactured in the United States were smoothbore guns. However, Whitfield and Bradley were able to adopt the relatively new invention of rifling to turn out a more accurate cannon than the old smoothbores. Rifling was a system of lands and grooves in a barrel which caused a projectile to turn as it exited the muzzle, thereby improving trajectory and accuracy. Rifled weapons had to be stronger than smoothbore because a greater stress was inflicted on the gun by a tighter seal (less windage) necessary for the projectile to take the rifling, resulting in vastly greater pressures in the breech to overcome the friction between the projectile and the rifled bore.

Beyond finishing the Brennan guns, there is evidence that Whitfield, Bradley & Co., cast at least four guns (two iron six-pounders and two bronze nine-pounders) of its own. The weapons served with General Lloyd Tilghman at Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and later at Fort Donelson. Tilghman described the guns as “pretty fair” but another officer remarked “…There was in the fort one large howitzer (a good one) and two small 9 or 12 pounders, made in Clarksville, of very little account…” (O.R., IV, 464, 514; VII, 388, 394).

A writer for the local paper, The Jeffersonian, disagreed whole-heartedly. An item in the July 9, 1861, paper noted, “Whitfield, Bradley & Co., are turning out some beautiful cannon. We examined some at their foundry, which will compare with any we have seen. They are prepared to make any quantity of the most approved models. They are also manufacturing balls and grape shot.”

Beach commented in The Tennessee County History Series: Montgomery County that the company was concerned with producing a good product, noting, “The accuracy of cannons was tested by firing at a tree across the Cumberland River” (p. 49).

Weapons were not the only contribution the company made to early war efforts. Beach wrote of the hardships on families of volunteers, many of which were destitute with men gone to fight: “However, the employees of Whitfield, Bradley and Company Foundry and Machine Shop, thankful of employment, contributed $58 to the fund of $25 deposited by the company officials. This donation collected on December 18th [1861] indicated concern for those who first suffered pangs of hunger” (Along the Warioto, p. 186).

However, their employment in producing cannons was not to last. Union troops occupied Clarksville shortly after the fall of Fort Donelson in February 1862. One of their first actions was to close the foundry, which stayed closed for the duration of the war. Thus the loss of Fort Donelson and Clarksville was a double blow to the struggling Confederacy; it not only closed the Cumberland River to Confederate traffic, it also closed one of the few foundries in the C.S.A. capable of producing badly needed artillery for the Confederate army.

Whitfield managed to hang on to the property until the end of the war, when he took on new partners, including his brother-in-law J. A. Bates. The foundry resumed operations in 1867 and has continued to turn out iron products of high quality into the 21st century.

1140 Red River Street Clarksville, TN 37040 931-647-1538 ![]()

© 2022 Clarksville Foundry. All rights reserved. Images may not be published, rewritten or redistributed, in whole or part, without the written permission of Clarksville Foundry or without proper credit given to Clarksville Foundry.

All orders accepted by Clarksville Foundry, Inc. are subject to our Terms and Conditions of Sale.

Clarksville’s first foundry, 1847.

Clarksville’s first foundry, 1847.